Credibility of Real Money

Despite everything central planning has thrown at them, the market continues to treat gold and silver as real money. How do we know this, and what does central planning have to do with it?

Gold and silver remain money because investment demand for both continues to rise as confidence in centralised systems erodes. This is especially visible in markets such as China and India. Organisations like GATA have long documented the pressure applied by central planners to suppress precious metals, while analysts such as Harvey Organ continue to track the mechanics of paper manipulation in gold and silver markets. Importantly, both metals still function as final settlement. All paper ultimately represents a short position against physical gold.

When the market recognises gold and silver as money—as it has throughout history—they operate as decentralised money. They do not require a central authority to legitimise their value. They hold value because the market chooses them as such.

The purchasing power of gold and silver is largely influenced by the credibility of centralised money. During a nation’s ascent, central planning appears effective because it is small relative to the broader economy. Limited intervention can be presented as beneficial. As conditions deteriorate, however, the response is always the same: calls for more central planning.

As centralised systems gain credibility, silver typically loses purchasing power first. This is because central planning begins locally, and silver’s historical role has been primarily domestic. As confidence in centralised systems expands further, gold also begins to lose purchasing power. Eventually, silver is reduced to an industrial metal and gold to an ornament. Even then, both metals continue to act as final settlement for the minority of the market that refuses to fully embrace central planning.

When centralised money captures the majority of monetary demand, gold and silver become marginalised. This marks the peak of central planning’s credibility. From that point forward, expansion requires enforcement. Central planning must use its accumulated credibility to protect itself.

This may sound circular, and it is. It does not work. When credibility begins to fade, central planning turns to its only remaining strength: its monopoly on force. The goal becomes preservation of the status quo at all costs. Gold and silver are resisted precisely because they expose the weakness of that system.

As centralised money loses credibility, gold and silver regain it. While the rise of centralised money can take decades, and the suppression of precious metals can last just as long, the reversal tends to be abrupt. Central planning expends increasing resources to maintain the illusion of credibility. If it fails to do so, credibility collapses immediately. By prolonging the illusion, the system survives a bit longer—but at the cost of a sharper eventual reckoning.

In this phase, gold and silver often return almost together. Gold responds first to the loss of international credibility; silver follows as domestic confidence erodes. Which metal moves first depends on whether confidence breaks internally or externally. As credibility decays, demand for precious metals accelerates. Eventually, centralised money loses the confidence of the majority.

This process is called hyperinflation. It is not sudden for those paying attention. It is the inevitable end state of prolonged pretense. Central planning continues to defer reality until it can no longer do so. The warning signs are numerous, but most people remain absorbed in the illusion.

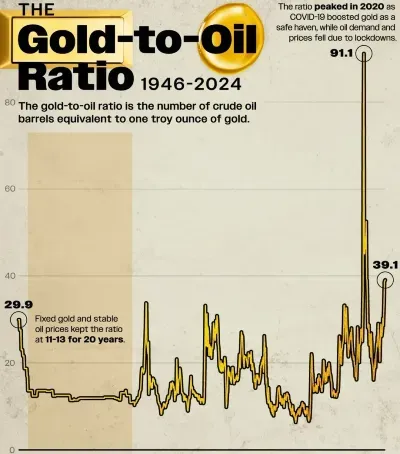

A rough chronology illustrates this progression in the United States: silver was demonetised in 1873; the Federal Reserve was established in 1913; gold was removed from domestic circulation in 1933 and from international settlement in 1971. Gold reached a real-term low around 1999–2000, coinciding with the introduction of the euro as a partial alternative to the dollar. Silver followed shortly after. Gold lost credibility last and has begun to recover first; silver lost credibility first and will recover later. Notably, the early 2000s also marked a sharp increase in legislative and institutional force.

Today, with gold and silver setting record nominal highs, the system appears closer to a broad loss of confidence.

Long-term charts—such as 650 years of silver prices adjusted for inflation, or the silver-to-gold ratio—suggest that neither metal has returned to historical norms. The ratio remains elevated, and real prices remain below previous cycle peaks.

Gold and silver are regaining credibility. Despite decades of fractional-reserve banking and synthetic bullion markets, the market continues to recognise them as real. GATA and Harvey Organ have compiled extensive evidence showing ongoing efforts to suppress that recognition.

Recent developments reinforce this trend. Central banks have halted metal sales in response to physical demand. Large institutions are increasingly taking delivery rather than holding paper claims. JPM closed their silver shorts, and switched to a long position after getting their wrists slapped by the Trump Admin.

The signal remains consistent: paper promises weaken, and real settlement reasserts itself.