Everything Moves in Cycles

If you spend time educating yourself and paying attention, certain patterns begin to stand out. Over time, recurring themes become difficult to ignore.

Three ideas, in particular, tend to surface again and again: everything is connected, everything moves in cycles, and there is very little that is truly new.

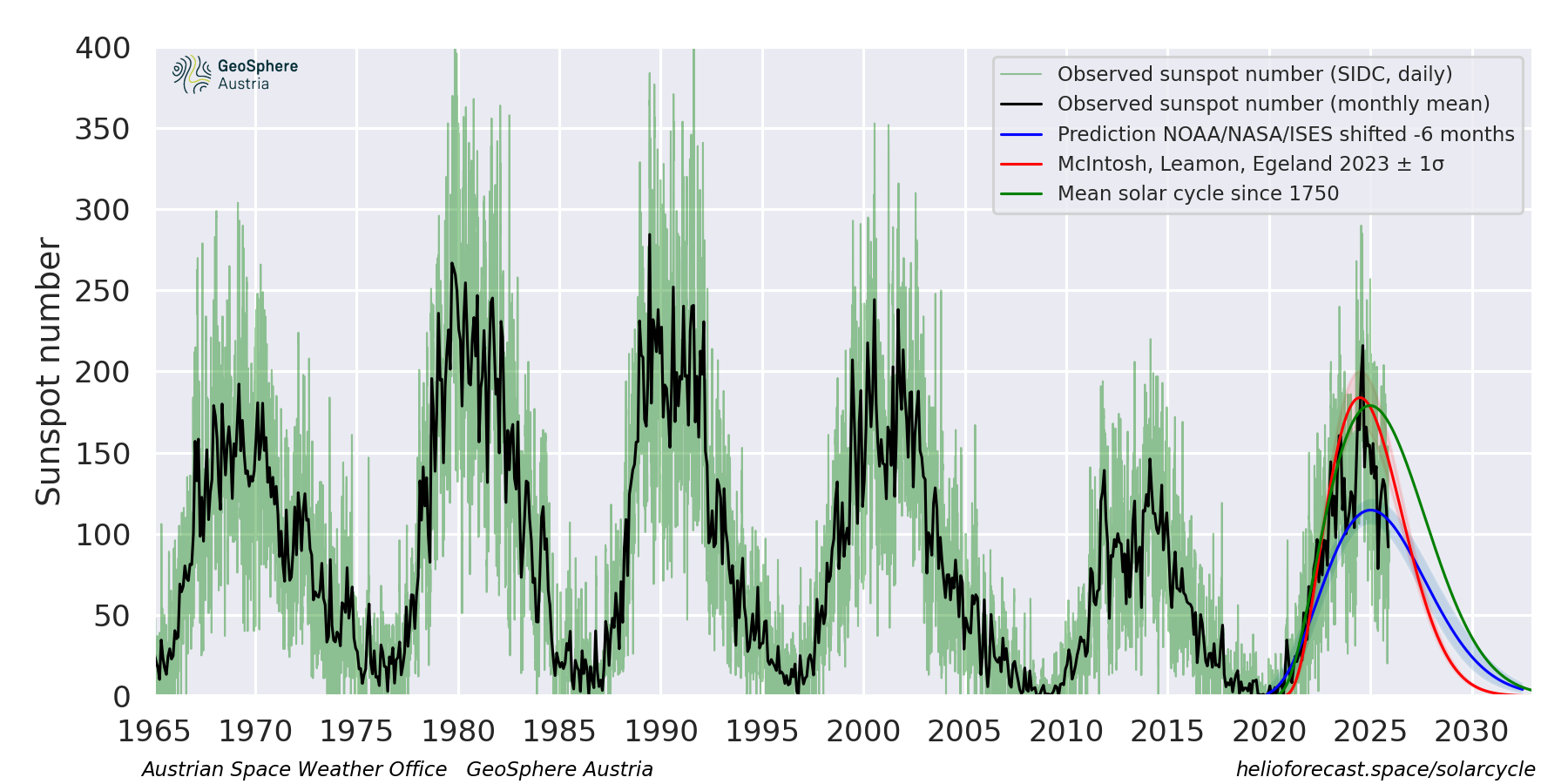

Consider climate as an example. The sun plays a central role in regulating Earth’s climate. Variations in sunspot activity and solar wind influence the amount of radiation reaching the planet, and there is extensive research linking these changes to long-term temperature patterns. Over the past century, public narratives have oscillated between concerns about cooling and warming—an oscillation that itself reflects cyclical thinking rather than linear change.

Observed data shows that periods of reduced solar activity often coincide with cooling trends, while increases in atmospheric CO₂ tend to follow temperature changes rather than precede them. For those interested in the details, there is a substantial body of material exploring these relationships.

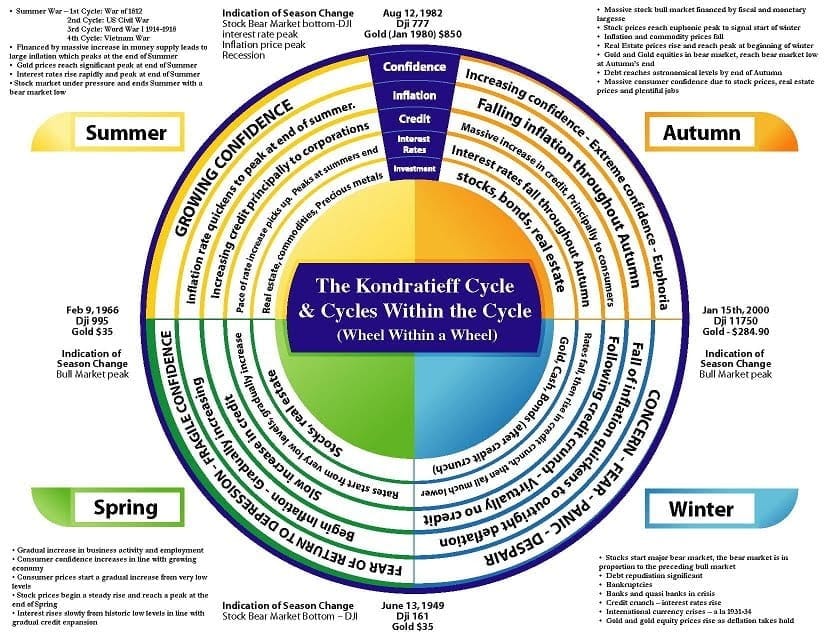

Life itself follows a familiar cycle: birth, growth, peak, decline, and death. These phases are mirrored in the seasons—spring, summer, autumn, and winter. What’s less obvious, but no less important, is that economies and civilizations tend to follow similar arcs, often over the course of roughly two centuries.

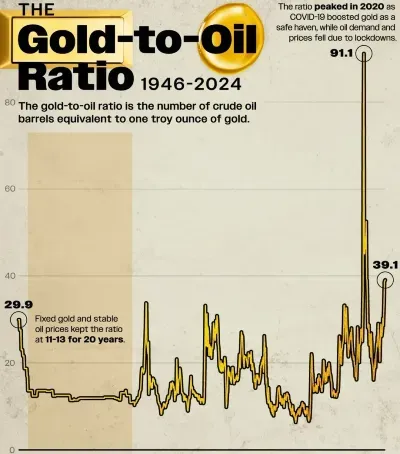

Understanding these broader cycles can materially improve long-term investment and business decisions. Historically, hard assets tend to perform best during the later stages of a cycle, while paper assets dominate during periods of expansion and optimism. Cycle-based analysis suggests that periods of apparent stability often precede more difficult adjustments.

In economics, Nikolai Kondratieff was among the first to systematically study long-term cycles. His work identified recurring waves of expansion and contraction that have appeared repeatedly throughout modern economic history.

Others have built on this foundation, developing models that attempt to measure confidence, capital flows, and turning points in market psychology. While the precise timing of such shifts is always uncertain, the broader pattern—expansion followed by contraction—has proven remarkably persistent.

What’s notable is how many otherwise independent schools of thought converge on similar conclusions. Austrian economists, cycle analysts, market practitioners, and long-term observers all point toward the same underlying rhythm: periods where real assets outperform paper claims tend to follow prolonged credit expansions, while paper assets dominate during earlier phases.

The more one studies history, the clearer it becomes that repetition is the rule, not the exception. With increased knowledge often comes a deeper awareness of how much has already been experienced before. Paths that feel unprecedented rarely are.

In simple terms:

“What has been is what will be, and what has been done is what will be done, and there is nothing new under the sun.”

— Ecclesiastes 1:9