Gold Constant, The Anti-Bubble

Editor's Note from 2025: The gold bubble in the 70s, when Nixon removed the gold standard, was not a gold bubble. It was the USD being oversold at that time. An asset being in overbought or oversold territory does not imply there is a bubble. And because we view gold as the constant, the reference point for value, our compass for value orientation, it is not possible for gold to be overbought. It is only possible for currencies to be in overbought or oversold situations, while in their long term downtrend against gold.

There has been increasing talk lately about gold being in a bubble, or eventually becoming one. Here is a different perspective.

For thousands of years, gold has functioned as money across most of the world. At various points, governments have experimented with paper money, and those experiments have always ended the same way—summed up neatly by Voltaire:

“Paper money eventually returns to its intrinsic value—zero.”

Sometimes the decline is gradual. More often, however, paper currencies return to zero through hyperinflation. Hyperinflation is a reversion to the mean. It occurs when, through a combination of excessive supply and declining demand, a currency becomes worthless.

Hyperinflation happens when supply overwhelms demand. This can occur through aggressive money creation, collapsing demand, or both. If demand remains relatively strong, it simply takes more inflation to reach hyperinflation. By demand, I mean both domestic use—exchange and savings—and international use—trade and reserves.

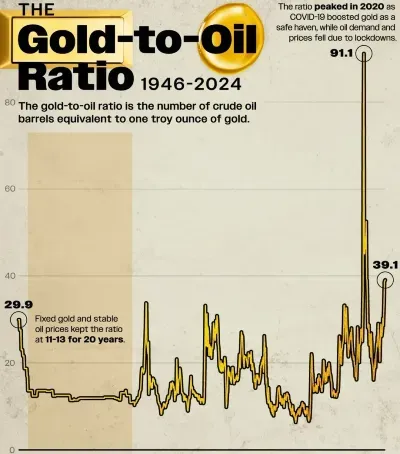

Oil plays a central role in this process. It is the backbone of modern economic activity. Limit oil access, and you limit growth. Reserve currency status matters because oil is settled in that currency and enforced through geopolitical power. Clues to the timing of hyperinflation lie in these supply-and-demand dynamics: oil politics, trade settlement, monetary expansion, and rising prices across the economy.

As paper currencies lose value, gold absorbs demand. During credit contractions—during the “winter” phase of a civilization—value flows from paper into gold. This is the inverse pyramid at work.

What makes the current situation different from most historical hyperinflations is that this is a slow hyperinflation of the reserve currency. It is not just the U.S. dollar at risk. Many currencies are backed by, or pegged to, the dollar. As the dollar devalues, these currencies must follow to preserve existing trade relationships. When the reserve currency loses credibility, currencies without independent economic strength—through productivity, demographics, or sound institutions—inflate alongside it.

The fall of Rome offers a useful parallel. When a reserve currency collapses, the consequences spread outward.

The U.S. dollar has existed as an unbacked reserve currency for roughly forty years. Gold has served as money for thousands. Gold is not in a bubble; it is in an un-bubble. Demand has been systematically diverted from gold into paper, and paper claims on gold now far exceed the available physical supply. This artificially inflates supply and suppresses price. When these paper structures fail, gold will naturally reclaim its role as the primary store of value and reserve asset.

FOFOA describes this dynamic clearly in his discussion of gold’s “un-bubble”:

“The gold bubble has not popped! …because gold is not in a bubble. There is no gold bubble. There is no such thing as a gold bubble. Never has been. Never will be.

Gold is the opposite of bubbles. It is the inverse—the recipient, the beneficiary—of frothy air that escapes when bubbles pop. It has already absorbed the collapse of two major bubbles this decade and stands ready to absorb more.

For those plotting a ‘blow-off top,’ consider this: there may be no blow-off at all. The pattern is not a spike—it is an orbital launch.”

— FOFOA

For another perspective on reserve currencies and market collapses, Martin Armstrong’s work is worth examining. His analysis of how markets fail aligns closely with FOFOA’s view: gold behaves opposite to paper. When confidence breaks, paper collapses inward while gold reasserts itself outward.

Armstrong’s discussion of the British pound is instructive. It did not hyperinflate because Britain entered a moratorium and eventually honored its obligations. It is worth asking whether similar choices are politically feasible elsewhere.

I’ll close with a quote from Friend of Another:

“This is the road ahead. A fiat no different from the dollar in function, yet a universe away in management. A wealth asset that stands beside money, yet carries no official label. In this way society circles the earth, only to begin again where it started—having learned that wealth money and man’s money were never the same.”

— FOA