Gold Price Fixing

Today we’re going to look more closely at two core ideas that feature here regularly.

The first is that the spot price of gold is largely irrelevant, because it has little grounding in physical reality. The second is that unless you are taking physical delivery, you do not own gold—you hold a claim on it.

What hasn’t been fully laid out is why these two points matter, and how they fit together.

In a genuinely free market—one governed by the principles of “do no harm” and “do all you agree to do”—gold would not have a spot price at all. Just as there is no “price” for the U.S. dollar, only exchange rates, gold would trade via exchange relationships rather than a centralised quote.

Exchange rates are simply the price of one currency measured against another. All other prices are expressions of a currency measured against goods, services, assets, or commodities. If the dollar did not hold a monopoly on money, gold would trade at an exchange rate, not a spot price. Whether gold has a price or an exchange rate depends entirely on whether it is treated as a consumable commodity or as money—something to be spent or saved.

When gold is treated purely as a commodity, it is assigned a spot price. That price is determined through a combination of mechanisms. The London Bullion Market Association (LBMA) sets a reference price twice daily—the London Fix—which influences the majority of global gold trade. Outside of that process, prices are established through bids and offers on commodity futures exchanges.

A gold future is intended to represent a contract for future delivery of physical metal. In practice, however, the largest participants in these markets are financial clearing houses and institutions, and the majority of contracts are settled in paper rather than metal. Daily trading volume in gold futures routinely rivals or exceeds annual global mine supply. This does not reflect physical turnover; it reflects leverage.

This is where central banks enter the picture. As lenders of last resort, they step in when physical supply cannot meet delivery demands at the quoted price. Paper settlement prevents default. There can never be a shortage of paper, because losses are absorbed and socialized. Physical shortages, however, do occur.

For a time, central banks can bridge the gap by selling or leasing gold into the market. This was particularly evident during the 1990s, when several Western central banks sold or leased substantial portions of their reserves. What was not sold outright was often leased. The purpose was not profit, but system preservation.

Today, the limits of that strategy are visible. A growing number of countries are seeking to repatriate their gold. Others are questioning custody arrangements and reserve accounting. These moves are not symbolic; they reflect concern over availability and control.

Some argue that the euro is stronger because it is “backed” by gold at market prices rather than a fixed valuation. This deserves scrutiny. The European Central Bank does not store gold directly; reserves remain with national central banks. If those reserves are held abroad, leased, or otherwise encumbered, the backing is more conceptual than physical.

Ultimately, central banks cannot sell or lease gold indefinitely. Physical supply is finite. Scrap flows and mine production have limits, and bullion holders are generally unwilling to sell into a market where the quoted price understates real scarcity. This is why gold has steadily risen over the past two decades.

As the paper price diverges from physical reality, gold increasingly goes into hiding. More contracts are settled in paper, fewer in metal. When a holder demands delivery and supply cannot meet demand, price must adjust. For now, enough metal exists to satisfy marginal physical demand. Over time, that balance shifts.

When confidence in paper currency erodes faster than price can compensate, the currency loses its role as a store of value. At that point, other currencies—or commodities—begin to assume that role, and gold resumes trading as money via exchange relationships rather than administered prices.

Finance ultimately answers to physics. What happens in the physical world constrains the abstractions built on top of it. Gold, when functioning as money, requires an exchange rate, not a centrally managed price.

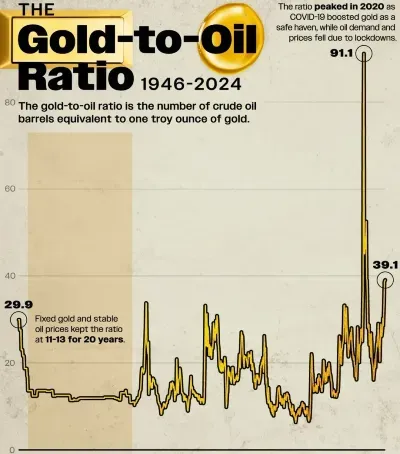

Some attempt to approximate this by pricing assets in gold—using ratios such as gold-to-oil or gold-to-equities. These are useful heuristics, but as long as paper-settled futures dominate the reference price, distortions remain.

Today, the closest approximation to a true exchange rate for gold is found at the margins: refineries, dealers, and physical suppliers. These actors deal in real constraints. Their prices reflect availability, premiums, delivery times, and actual demand. Watching these signals tells you more than watching a screen quote.

If you still need a reason to think about physical delivery, consider the shape of monetary inflation. Historically, it is not linear. It accelerates. On a chart, it appears as a curve—slow at first, then steep. Many indicators suggest we are entering that steeper phase.