Physical Gold & Silver

Recently, I found myself back at a local coin shop, exchanging inflating dollars for real money. There’s something grounding about walking into a small space where the shelves are lined with tangible wealth—coins, bullion, and pieces from around the world. It’s a reminder of what money looks like when it exists outside a screen.

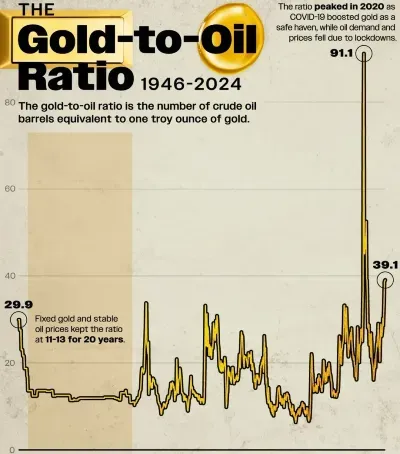

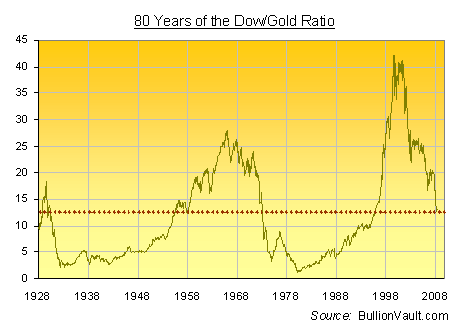

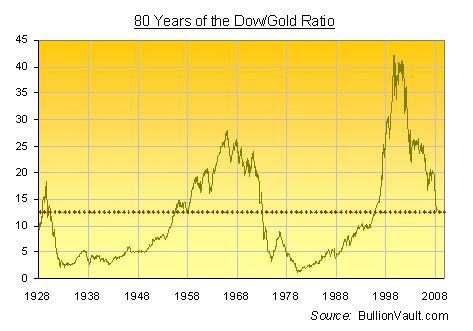

Gold and silver have been in a sustained uptrend since the turn of the century. Since roughly 2000–2001, equities have largely moved sideways, while commodities—including precious metals—have advanced steadily. The Dow/Gold ratio illustrates this inverse relationship clearly: periods of strength for equities tend to coincide with weakness in gold, and vice versa. Historically, when viewed through this lens, the adjustment process for equities appears unfinished—an environment that has traditionally favored gold.

Gold and silver have reached repeated nominal highs in recent years, which raises an important question: what do nominal versus real prices actually tell us?

Nominal prices reflect today’s prices measured in today’s dollars. They don’t account for changes in purchasing power. Viewed this way, gold and silver appear to be at record highs, which leads many to believe it’s too late to buy—or even that it’s time to sell.

Real prices, by contrast, adjust for changes in purchasing power. Comparing gold priced in past dollars—such as those from 1971 or the early 2000s—provides a clearer perspective. When adjusted properly, gold is still well below its real highs from previous cycles. Nominal comparisons alone can be misleading when the unit of measurement itself is constantly changing.

Another useful perspective comes from market participation. Compared to other asset classes, gold’s share of global investment remains relatively small. During prior peaks, public participation was widespread. Today, most people rarely encounter physical gold, let alone hold it. There is a qualitative difference between paper claims and something tangible. Physical metal feels real in a way paper never does—solid, finite, and outside the system. Paper currency, by comparison, continues to lose purchasing power over time.

From a long-term perspective, the gold trend appears intact. It has not reached the real extremes seen in earlier cycles.

And silver hasn’t been forgotten. Silver has historically followed gold, often with greater volatility. Where one moves, the other is rarely far behind.

Beyond price trends, gold and silver have consistently served as stores of value during periods of economic stress. When inflation, taxation, and regulation increase, precious metals tend to retain liquidity and purchasing power. At the same time, physical metal often becomes harder to source, as holders prefer to part with depreciating currency rather than assets they trust.

Put simply, physical gold and silver are easiest to acquire before they’re urgently needed.