Real Price Discovery

How can anyone reasonably know how to buy low and sell high when so many markets around the world are distorted by government intervention? Judging value becomes difficult when prices are consistently pulled out of balance. While markets are never perfectly balanced—conditions are always changing—there still needs to be a reliable way to judge price. Otherwise, we have no real sense of what we are paying for anything.

Ultimately, it comes down to the unit of account you choose. If you use government-issued paper currency as your unit of account—most often the U.S. dollar—you only ever see one perspective. Quite often, that perspective works in favor of the issuer, leaving you holding the empty bag and wondering how you lost yet again. Prices measured this way are commonly referred to as nominal prices, and they are the prices most people are familiar with.

Viewed through nominal prices, the picture looks reassuring. Bonds, stocks, and real estate—the three favorites of conventional investors—are all near their historical highs relative to recent decades. Short- and long-term trends priced in dollars appear to move steadily upward. After all, they never seem to go down. This aligns neatly with mainstream media narratives and the advice repeated by most professional financial planners.

The uncomfortable truth is that they may be right—at least within that framework. As long as more debt is created to service existing debt, prices measured in dollars are likely to continue rising. This isn’t limited to the United States. Because many currencies remain tied, formally or informally, to the dollar, they follow the same trajectory. Whether measured in dollars, euros, or another fiat currency, prices of both real and paper assets will continue to inflate as long as this system persists. To delay the inevitable consequences of artificial debt expansion, negative real interest rates and accelerating money creation become unavoidable.

Another approach is to use inflation-adjusted currencies, often referred to as real prices. This method attempts to strip out changes in purchasing power. While useful over short periods, it quickly runs into a practical problem: where do you start? Do you anchor prices to 1971, when the dollar was last linked to gold? To 1980, because it feels convenient? To 2000, 1913, 1912, or 1944? Each choice changes the story. Nominal prices show relationships at a single moment in time; inflation-adjusted prices offer only a partial view across limited periods.

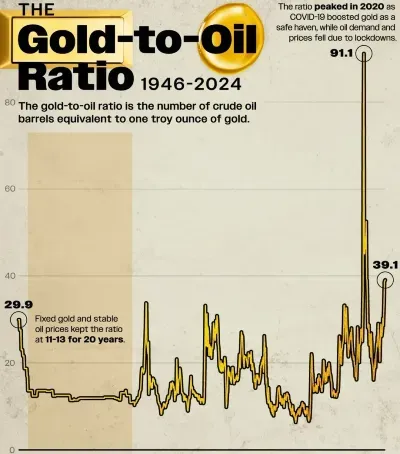

For long-term comparison, gold stands out as the most stable unit of account. Its price may fluctuate, but relative to paper currencies it is remarkably consistent. Unlike fiat money, whose supply can expand or contract dramatically based on political decisions, the physical supply of gold changes slowly—typically increasing by about 2% per year through mining. Paper currency supply, by contrast, can move from gradual expansion to exponential growth almost overnight.

Because of this political volatility, demand for paper assets tends to swing violently—think Tulips, Mississippi, Weimar, Argentina, or more recently bonds, stocks, and real estate. Gold is far less sensitive to politics. When investors lose interest, jewelers and industry provide demand. Today, investment demand has returned with intent and conviction. Those buying gold now tend to understand why they are buying it, creating steadier demand. Supply and demand in the gold market change slowly, making it a more reliable long-term measure of value.

Gold can also do what both nominal and inflation-adjusted pricing attempt to do, without requiring constant conversion. Better still, you don’t need to own gold to use it as a unit of account. Services like Golden Markets and Priced in Gold show asset prices, utilities, housing, and energy measured directly in gold. Viewed this way, some everyday costs—such as electricity or gasoline—are lower today than they were years ago.

For conventional nominal pricing, resources like PricedinGold.org or GoldPrice.org provide real-time charts and a range of market perspectives. They are useful tools—as long as you understand the limitations of the unit being used.

Applying this framework to saving makes the problem clearer. Traditional savings accounts make little sense. Even at low official inflation rates, purchasing power declines over time. Add negligible interest and recurring fees, and savings become a slow bleed. Using higher estimates of inflation, real returns on savings are clearly negative. Savers are effectively forced to invest simply to maintain purchasing power.

This leads naturally to real assets. Saving in gold, silver, or other precious metals flips the odds. Instead of absorbing the effects of currency dilution, you stand on the other side of it. The reason is straightforward: precious metals have limited supply, while paper currency can be created without limit. While the paper price of metals can move anywhere, the physical value cannot be printed away.

Politics complicate price discovery further through paper markets. Futures, options, certificates, and other synthetic instruments distort price signals. The result is a paper price that often diverges from physical reality. Evidence of this appears in persistent shortages, rising dealer premiums, and strong physical demand at prices that supposedly reflect ample supply. In practice, the dealer premium matters more than the quoted spot price. That premium is the real signal.

Another valuable indicator is the bullion basis and backwardation, as described by Dr. Antal Fekete. The basis measures the difference between the spot bid price and the futures ask price. Normally, futures trade above spot, indicating available supply. When the basis turns negative—backwardation—it signals that buyers are willing to pay more now rather than risk not obtaining metal later. Physical scarcity is asserting itself.

Fekete, James Turk, and FOFOA have all written extensively on backwardation in gold and silver. While technical, the message is simple: when future supply disappears into present demand, price signals are being suppressed.

Looking beyond gold and silver, other precious metals can also be evaluated using gold as a unit of account. Relative to abundance and historical ratios, silver appears the most undervalued, followed by platinum. Palladium appears closer to fair value. These metals offer an alternative to paper assets and protection against monetary dilution. Whether or not a full monetary reversion occurs, precious metals retain value across systems.

To close, a concise observation from Another captures the essence of unit-of-account thinking:

“Gold bids for dollars. If gold stops bidding for dollars, the price (in gold) of a dollar falls to zero. There doesn’t need to be a stampede into gold for gold to become priceless. Gold is the only medium that currencies do not move through. It is the only money that cannot be valued by currencies. Gold denominates currency—gold moves through paper currencies.”