Rising Interest Rates

Editor's Note from 2025: Not only are rising rates not politically correct, but the math doesn't work without lower rates. The sheer volume of principal outstanding is almost $40T now, that's $40,000,000,000,000. Add to that high levels of household, and private credit. Best case is a slow reversal of this trend, which implies stagflation via steady or slightly rising rates. More likely are the hiccups along the way, some we continue to see. Smaller blow ups, bankruptices, liquidity issues, all quietly getting papered over.

We are still witnessing the same currency war, except today it is being called a trade war under the guise of tariffs, and yesterday it was called Covid stimulus. And most importantly its a currency war that has been less between nations as between the central bank and the savers. Aggressive inflation means the savers bailout the debtors. Just have a look at the ledger to see which end you're on, or if you're observant enough to position on neither end.

And of course the part about America reasserting its military prowess, that is in full swing and is such an obvious historic rhyme with many empires of the past. Ignite some patriotic narratives, print money and hope for the best. Is it printer go brrr, or keyboard go clickety clack, or just a silent thumb swipe?

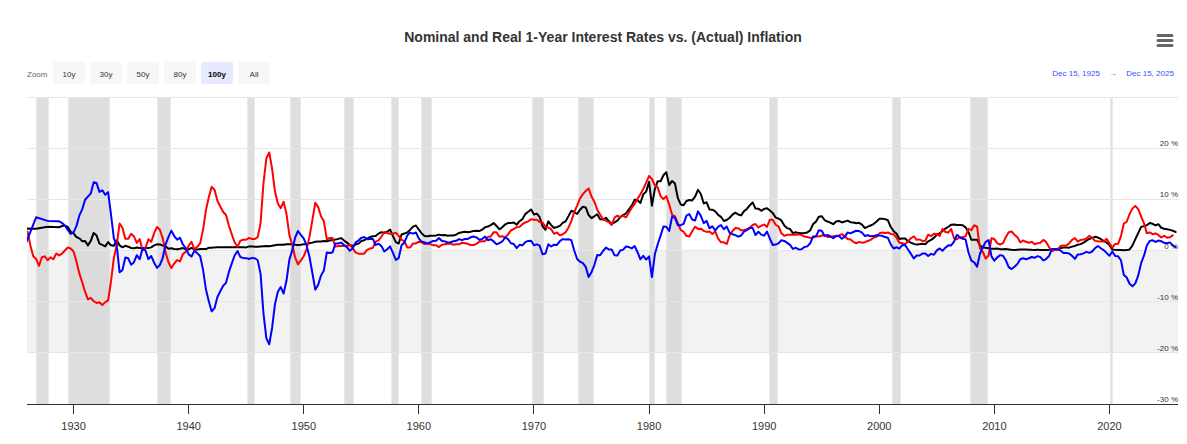

I find it very interesting that over 100y the real interest rate has not gone above 5% except during the the 80s Volker interest rate hikes, and pre-WW2. It's amazing to me that anyone would be willing to lend to the government with such measly returns. Sure its relatively safe given the Fed will step in as lender of last resort. But I can think of much better asymmetric opportunities.

Consider this quote:

“There is no means of avoiding a final collapse of a boom brought about by credit expansion. The alternative is only whether the crisis should come sooner as a result of a voluntary abandonment of further credit expansion or later as a final and total catastrophe of the currency system involved.”

— Ludwig von Mises

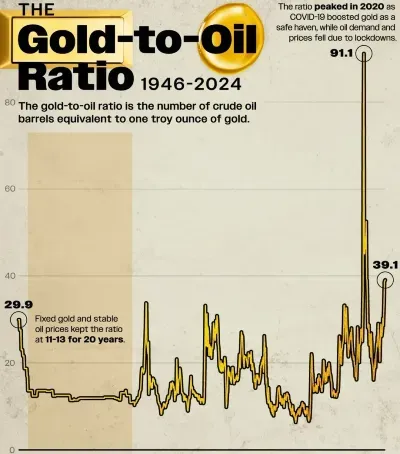

What we are seeing today is a currency war. Governments attempt to devalue their currencies faster than others in order to protect export markets. The logic is straightforward: if your currency (A) is cheaper than your trading partner’s currency (B), your goods become cheaper for them to buy. Because B’s businesses do not accept A’s currency, A must buy B’s currency first. This creates an exchange-rate advantage that temporarily boosts exports.

The problem is that A’s currency eventually comes home. Since B has little use for A’s currency, it is spent back into A’s economy through goods, services, or investments. If exports are financed with newly created money, prices eventually rise as more currency circulates. The temporary export advantage is offset by higher production costs driven by inflation.

Another problem emerges when every country adopts this strategy. It becomes a race to the bottom. Currency devaluation earns its name honestly: the more nations participate, the faster all currencies lose value. The end result is not competitiveness, but widespread debasement.

So why do governments persist? One reason is the short-term boost in sales. It feels like recovery and preserves confidence. The other reason is debt. Governments, businesses, and individuals are deeply leveraged. It’s not only households living paycheck to paycheck; many corporations and governments operate with little margin for error.

Interest rates represent the cost of borrowing. If borrowing costs rise, highly indebted entities quickly become insolvent. Increasing the money supply keeps interest rates low by ensuring abundant credit. Analyses suggest that even modest interest rate increases would severely strain government finances across much of the developed world.

Returning to the original quote, governments face two options. They can continue expanding the money supply—often by purchasing government bonds—to suppress interest rates and extend the credit bubble. Or they can stop intervening, allowing rates to rise naturally. The latter would likely result in widespread defaults across governments, businesses, and households.

Government ultimately operates on confidence. As long as dissatisfaction remains manageable, the system can continue. An outright default brings hardship and unrest. History shows that populations respond poorly to sudden economic collapse. From a political perspective, postponing the reckoning becomes the preferred option.

As a result, central banks continue to intervene—maintaining low interest rates and implementing policies similar to past quantitative easing programs. These actions are designed to delay correction rather than resolve underlying imbalances.

There is, however, one wildcard. The United States remains the dominant military power in the world. Its military spending exceeds that of all other nations combined. When long-postponed corrections finally arrive, that power will not sit idle. The U.S. is unlikely to default quietly. Instead, the pressure may manifest as increased aggression abroad and tighter control at home.

When the dust settles, the landscape will look very different from today.